Category: Practice

Upcoming Zoom Webinars, Autumn 2023

This autumn, the OptiBreech Collective will host three webinars to share learning from our on-going research and address common concerns. These webinars are designed for professionals attending planned or unplanned vaginal breech births but are open to all.

This autumn, the OptiBreech Collective will host three webinars to share learning from our on-going research. These webinars are designed for professionals attending planned or unplanned vaginal breech births but are open to all. We will address three common fears and concerns about vaginal breech birth.

Translated caption options will be available.

Three types of cervical head entrapment in vaginal breech births

Thursday, 26 October 2023 from 13:00 to 14:00 GMT

- Preventable

- Manageable

- Unpredictable and potentially catastrophic

Which have you encountered? Would you know how to prevent and/or manage if needed?

Human factors when forceps are needed in vaginal breech births

Wednesday, 22 November 2023 from 13:00 to 14:00

When you have been involved in forceps deliveries of the aftercoming head, how has the communication worked? Did everyone know their role? We will share our learning with you about how to optimise communication and attention when there is a tight fit just at the end.

How to resolve complicated arm entrapment in vaginal breech births

Monday, 11 December 2023 from 13:00 to 14:00

When your initial attempt at releasing the arms do not work, what are your options? We will talk you through our strategies and experience.

How can you join?

If you are staff at a current OptiBreech site or your site has submitted an expression of interest for our planned stepped-wedge cluster trial, your OptiBreech lead/contact has received calendar invites with the Zoom webinar links.

If you are subscribed to one of our online courses, you will find these links within the course, as below. There, you can download a calendar invite with the Zoom link.

On Call for Breech Births

A key element of OptiBreech Care is providing additional skilled and experienced staff at planned vaginal breech births (and unplanned ones too if we can manage it!) in line with the RCOG guidance.

We know this supports safety but traditionally it has been hard to achieve as the numbers of vaginal breech births may be few and far between, meaning limited experience and often limited or brief training. Most hospitals have < 1 hr a year for each of the common obstetric emergencies as part of their mandatory training, maybe less depending on each hospital’s rolling program of multidisciplinary skills and drills. Furthermore, expecting whoever is on and available to care for families having a Breech birth puts significant extra stress and strain on the on-call labour teams, often already pressured with complex scenarios and sadly short-staffed wards.

We often get asked- How to do the on-call elements of the OptiBreech care pathway work? Who will cover it? Everyone is doing enough already?!

Each of our current sites may operationalise its on-call systems slightly differently, however, the core elements are the same.

All sites need to create a Breech team- ideally, this consists of a mix of midwifery and obstetric staff willing to be on call for breech births. Ideally, each member will have had some prior experience of a breech birth (although this is not always possible). All members of the Breech team should have completed a recent OptiBreech study day, online or face to face and have had an opportunity to practice rotational manoeuvres via simulation before providing on call for births. We would expect team members to counsel women appropriately regarding experience and expertise as part of the initial personalised care planning.

We would advise that initially, the On-call Breech teams are smallish. You may start with one or two lead people who are first on call with a wider group of staff that want to gain experience and eventually join a full on-call system.

We have found that this is the most successful way to safely develop confidence and competence amongst the team whilst also building a sustainable service. Often when launching the team in a service that hasn’t previously been supporting vaginal breech births, it can take a while for any to come along. Too large a team means that it is hard for people to gain regular exposure and experience and in the long run it takes longer to develop expertise.

Structure and payment of on-calls

All sites have currently been opting for a voluntary on-call system. At my site, many of the team have other on-call commitments (as manager on call or perhaps homebirth on calls) so they try to combine the calls and to date, no one has minded being voluntary on call. If called into the birth, they are always added to the roster to ensure liability coverage and this has worked wonderfully for the intrapartum teams as they are always grateful to have an additional presence with expertise available to support the team!

We have found this system has been provided at no extra cost to the service and has increased staffing on shifts which would have otherwise been under the template. Two of our core Breech team midwives work full-time in Intrapartum services so they have been available often when needed just by the pure nature of their roles and shift patterns. Whilst it is difficult for clinical midwives to be on the call before a shift, both midwives work full time so are already working a significant number of shifts. If one of the families booked for a vaginal breech comes into labour, the labour ward team always work to release them to support with birth as required. Another of our team works as a specialist midwife Monday to Friday and again has often been available during her working hours to support Breech births when needed or if called out overnight is able to rearrange her day as needed.

You will require one lead practitioner who can coordinate the Breech team and ensure appropriate care and on call coverage. Usually this will be the midwife leading the Breech Clinic but it could be an alternative depending on your context. The lead practitioner will provide details of the on-call service and then arrange with the wider team any dates they can’t cover.

In some sites, Breech teams prefer for women to contact them directly when they are in labour and the on-call team alerts the rest of the service, in other teams, the families will contact the triage service as per usual and then the Breech team will be alerted. Your system will depend on how your team is developed and your current on call working practices.

When women are in labour, other team members are invited to attend for additional experience and support, again this is facilitated voluntarily but we have found no problem with people wanting to be involved.

What if we have no one available or we don’t make it in time?

Sites need to make a realistic effort to try and support this as we know it improves safety outcomes and it is the core process outcome for the Optibreech care package but also women are honestly and realistically counselled. If no one from the team is available ( we know last minute dramas can happen) the care would fall to the rostered labour ward team and if they have limited experience in vaginal breech birth, they would counsel them as per their practice, which would usually be to recommend a cesarean birth.

Results from the feasibility study showed that across all sites a Optibreech team member was present for 87.5% of planned vaginal Breech Births.

We have found vaginal breech births have risen from 2 in 2021 to 10 successful (18 planned) last year with no admissions to special care and we have around 1/2 women a month planning a vaginal Breech birth. As our numbers have increased, we have been able to support more midwives and doctors able to lead the care and meet the full OptiBreech proficiency criteria. We are now considering implementing a more traditional on-call system to cover the whole month.

** A key aspect of care is the OptiBreech team member is addition to the case midwife. This is a pivotal part of the safety mechanism. The OptiBreech team member supports situational awareness, liaison with the wider MDT and ensures prompt action is taken if concerns arise**

Other OptiBreech sites operate similar variations to the above model, partly depending on their Breech birth numbers, initial expertise in the team and also taking into consideration individual contexts and staffing models.

Key aspects required for a Successful Optibreech On-Call Team

- Motivated individuals with a desire and flexibility to work this way

- A lead clinician to coordinate care, on-call availability and liaison with families

- A small group of staff initially to enable ongoing enhancement of competency- this group could be expanded as numbers and confidence grow.

We are currently inviting expressions of interest to join the next phase of the research. There will be funding, clinical training and support to implement this model of care. See here for more information or express your interest: https://optibreech.uk/2023/03/06/optibreech-cluster-trial-call-for-expressions-of-interest/

Safety Alert: meconium and tachycardia in breech births

Dr Shawn Walker explains why the combination of meconium and tachycardia, particularly in the first stage of labour, indicates increased risk in breech births. OptiBreech teams offer women a caesarean birth when these occur together.

Please join the OptiBreech Collaborative fetal monitoring case review seminar on Wednesday, 22 February, 8.30-9.30 – via Zoom.

Revised flowchart for decision-making in the second stage of breech births – revised Algorithm. The OptiBreech Collaborative welcomes your thoughts on this new version.

Permission given to share this post and video freely with anyone who may find it helpful, including women in your care or colleagues.

Transcript

Hello. My name is Shawn Walker. I’m a Consultant Midwife, the Clinical Lead and the Chief Investigator of the OptiBreech Trial.

In this video, I am going to speak directly to women who may be planning a vaginal breech birth under OptiBreech care, but the information is also to inform the healthcare professionals who may be caring for you.

Within the OptiBreech Trial, we have observed an increase in complications among births where either meconium-stained amniotic fluid or fetal tachycardia are observed during labour, and especially when they are both present. I’m going to explain each of these things in turn so that you understand exactly what we are looking for and why our OptiBreech teams will be giving you advice they give you if they occur during your birth.

Meconium

First, meconium. Meconium is the baby’s first poo. When it first comes out, it looks like thick black tar. In a textbook, ideal vaginal breech birth, where the baby has coped beautifully in labour, this black tar substance first emerges around the same time we begin to see the place it emerges from! At this point, your baby is being tightly hugged in the final few moments before they are born, and it basically gets squeezed out of them like a tube of toothpaste. We’re fond of calling it ‘toothpaste meconium.’ This is completely, 100% normal and will occur in every breech birth.

However, when babies pass meconium before they are born, that’s a bit less straightforward. The meconium mixes with the fluid around your baby, the amniotic fluid. Professionals call this, meconium-stained amniotic fluid. It’s a fairly common occurrence. We see meconium in about one out of seven pregnancies. Occasionally, babies pass meconium when they are still inside after 40 weeks of pregnancy, or past their expected date of birth. Their bowels are more mature and ready to get moving, so they do. Sometimes it doesn’t mean anything more than a bit of extra mess.

But sometimes, passing meconium during labour is a sign that baby is finding it a bit stressful. Again, most of the time, babies can handle a little bit of stress in labour, just like their mothers. But if meconium is identified early in labour, we have advised our OptiBreech teams to err on the side of caution and offer you a caesarean birth. This is because we have observed that when we see meconium early in labour, we observe additional complications later in labour more often. There still may be a long way to go, and most women tell us they would prefer to avoid a rushed, emergency caesarean birth late in labour. The earlier we do a caesarean if it looks like it may be necessary, the more calm and relaxed everyone can be, and the safer it is for you and your baby.

So we want to offer you the information that there is some increased risk of this happening if meconium is present early in labour. But of course, this decision is always up to you. You may want to ask your OptiBreech team for more information about other signs that your baby may or may not be coping well with labour before you make this decision.

Tachycardia

The other way that your team can tell if your baby is happy during labour is by evaluating the baby’s heartrate. If you have chosen to start your labour with intermittent monitoring, using a hand-held monitor, the presence of meconium in your baby’s fluid would be a reason to recommend continuous monitoring. Professionals often refer to the trace from continuous fetal heart rate monitoring as a CTG, which stands for cardiotocograph. There are a few things we look for in a CTG trace to tell if your baby is coping well. But one of the things we consider important in a breech birth is called the baseline.

The baseline of your baby’s heart rate is another way of saying the average heart rate. Normally, this ranges from about 120 bpm to 160 bpm in labour. Just like ours, your baby’s heart rate fluctuates in labour. When your baby moves, the heart rate on a CTG often goes up, or accelerates, just like yours would if you are climbing a flight of stairs. We consider this a really positive sign of your baby’s well-being.

But if your baby’s heart rate climbs up to over 160 bpm and stays in that range, rather than settling back down to where it was when we first listened in during your labour, that is another sign that your baby is finding things a bit stressful. We call an average heartrate over 160 bpm a fetal tachycardia. Tachycardia is always a sign that your baby is compensating for something. This is likely to be either an infection or hypoxia, which means oxygen deprivation. Your baby can’t breathe faster, so instead their heart beats faster to circulate the available oxygen. Again, most babies cope well with this for limited amounts of time. That’s what they are designed to do.

However, if your baby is experiencing more than thirty minutes of tachycardia that does not settle in the first stage of labour, the team will offer you a caesarean birth. If this is the only concern in your labour, for example the fluid around your baby is draining beautifully clear, and we see lots of accelerations on the CTG as well, your care providers may be comfortable with observing for a bit longer. This is especially likely if your labour appears to be progressing very quickly or if your baby is near to being born.

Meconium AND tachycardia

But when these occur together – tachycardia AND meconium in labour – your OptiBreech team will change from offering you a caesarean birth to advising one, especially if these occur in the first stage of labour. When BOTH tachycardia and meconium are present, they are both more likely to be associated with infection and inflammation.

When meconium is present in labour, in most cases, it has no consequence for the baby. But in 5% or 1:20 cases where we observe meconium in labour, the baby inhales meconium during the birth process and shows signs of what we call meconium aspiration syndrome after the birth. Meconium aspiration is more likely if the baby becomes severely stressed due to low oxygen levels and tries to take a breath before they are born. They then inhale the meconium-stained fluid into their lungs. This can result in breathing problems and require admission to the neonatal intensive care unit. This is more likely if infection or inflammation processes are present. In about 1:5 cases of meconium aspiration, there can be long-term problems for the child associated with this, again more likely if infection and inflammation are present.

We also think this may be more likely in breech births because of the way these babies are born. In every breech birth, there will be a period just at the end when the baby’s cord is likely to be compressed. When deciding whether it is safe to start or continue pushing, your OptiBreech team will be evaluating how long this period is likely to be, and how well your baby is likely to cope with it. Again, most babies cope very well with this for a short period of time, especially if we keep their umbilical cord attached after birth. But if your baby is ALREADY compensating with a raised heart rate and THEN the birth is difficult at the end, your baby may be more likely to inhale meconium-stained fluid.

For many years, the primary strategy to reduce risk in vaginal breech births was to try to predict which babies would have problems based on ultrasound scans – this baby is a bit bigger than others, this baby has a foot tucked below his pelvis, etc. But unfortunately, this strategy is not very accurate. A lot of caesarean births are recommended when the babies are not at significantly different risk to other babies who do not have these characteristics before labour.

In OptiBreech care, our strategy is to respond to emergent risks in labour. This means we look out for signs during the course of labour itself that your baby may be one of the few who do not do well with a breech birth, and we give you this information as soon as possible. Prior to labour, we simply cannot predict which labours may be affected by meconium or tachycardia. The situation in which a baby inhales meconium during birth and has some long-term issues as a result only occurs in about 1:700 births; and that includes all births, not just breech.

Meconium is only present in about 1 in 7 births, so when we see this in the first stage of labour, we know that the risk is now about 1:100. We know that aspiration of the meconium will only occur in about 1:20 births where the meconium is present, but when tachycardia is also present, this risk is closer to about 1:5. If one or both of these appear close to the end of labour, it may not be as much of a risk because most of the meconium may be coming down and out rather than circulating in the amniotic fluid around the baby. Your team may judge that your labour is progressing quickly and the safest thing is still continue with a vaginal birth. But when both meconium and tachycardia appear in the first stage of labour, our clear recommendation is for the team to calmly take you down the corridor and assist you with a caesarean birth, with your consent, due to the 1:5 risk of meconium aspiration with potential long-term problems.

I hope this helps explain why we consider meconium and tachycardia signs of potential risk for your baby, especially when they occur together, and even more so when they are present early in labour. I want to reassure you, that most babies will be absolutely fine, even if meconium or tachycardia occur during labour. Most babies are very resilient, like their mothers.

But the premise of OptiBreech care is that we are always honest with you about any potential increased risks that we detect. And we ask our teams to always honour your wishes about what you want to do with that information. We feel confident to support more people to attempt a vaginal birth because together, the OptiBreech collaborative are developing new guidelines, based on what we see happening in our research, to help keep you and your baby as safe as possible.

References

Beligere, N., Rao, R., 2008. Neurodevelopmental outcome of infants with meconium aspiration syndrome: report of a study and literature review. J. Perinatol. 2008 283 28, S93–S101. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2008.154

Buhimschi, C.S., Abdel-Razeq, S., Cackovic, M., Pettker, C.M., Dulay, A.T., Bahtiyar, M.O., Zambrano, E., Martin, R., Norwitz, E.R., Bhandari, V., Buhimschi, I.A., 2008. Fetal heart rate monitoring patterns in women with amniotic fluid proteomic profiles indicative of inflammation. Am. J. Perinatol. 25, 359. https://doi.org/10.1055/S-2008-1078761

Lee, J., Romero, R., Lee, K.A., Kim, E.N., Korzeniewski, S.J., Chaemsaithong, P., Yoon, B.H., 2016. Meconium aspiration syndrome: a role for fetal systemic inflammation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 214, 366.e1-366.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.AJOG.2015.10.009

Pereira, S., Chandraharan, E., 2017. Recognition of chronic hypoxia and pre-existing foetal injury on the cardiotocograph (CTG): Urgent need to think beyond the guidelines. Porto Biomed. J. 2, 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PBJ.2017.01.004

Reflections on International Day of the Midwife, 2022 — Breech Birth Network

Shawn talks about some of the challenges of improving the way we deliver care for mothers and their breech babies.

Yesterday was International Day of the Midwife. I saw but didn’t participate in the social media celebrations. Not because I wasn’t feeling it, but because my clinical academic midwife life was full to the brim. 931 more words

Reflections on International Day of the Midwife, 2022 — Breech Birth Network

Continuous cyclic pushing: a non-invasive approach to optimising descent in vaginal breech births

Continuous cyclic pushing is a non-invasive tool for expediating breech births with minimal hands-on intervention, or for confirming in a timely manner that further intervention is required to achieve a safe outcome.

- Shawn Walker, RM PhD, King’s College London and Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, West Middlesex Hospital

- Sabrina Das, MB ChB, MRCOG, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, Queen Charlottes & Chelsea Hospital

- Emma Spillane, RM MSc, Kingston Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

- Amy Meadowcroft, RM, Northern Care Alliance NHS Foundation Trust

Background

In the United Kingdom (UK) National Health Service (NHS), we have been working towards a collaborative, multi-disciplinary trial for breech presentation at term. Our complex intervention*, based on physiological breech birth practice tailored for a hospital-based care pathway, is called OptiBreech Care. In the OptiBreech Care Trial (IRAS 303028, ISRCTN 14521381) feasibility study, vaginal breech births are facilitated using physiological breech birth approach. This approach has been developed through prior research and testing of strategies described by others, 1–4 including midwives practising in out-of-hospital settings. As a result, it differs from assisted delivery techniques most hospital-based clinicians are familiar with. This creates a need to clearly articulate each component for effective implementation in practice. The purpose of this article is to articulate the theory and practice of one element of our complex intervention that we consider essential to the method: continuous cyclic pushing. Although different from most clinicians’ habit of ‘waiting for the next contraction,’ continuous cyclic pushing can easily be incorporated into assisted breech delivery practice.

* In clinical trials, an ‘intervention’ is the thing you do differently to try to change the outcome. Complex interventions contain more than one component, and the effect is thought to be the sum of the parts. OptiBreech Care is a care pathway intervention – a new care pathway for women and others whose babies are breech at the end of pregnancy.

Physiological Breech Birth

In a 2012 article, UK midwife Jane Evans described an approach to supporting spontaneous vaginal breech births as ‘physiological breech birth.’5 This approach centres on the normal mechanisms and movements of both mother and baby, in contrast to assisted breech delivery, where the birth attendant routinely manoeuvres the baby. Upright maternal birthing positions, such as kneeling, are frequently used, in contrast to routinely directing women to assume a supine position. Evans described how a normal breech birth exhibits ‘steady progress with each contraction.’5(p20) She also described how mothers move in response to the movements a healthy baby makes, especially the ‘tummy crunch’6(p48) or full body recoil flexion.3 Evans, who practiced for decades as an independent midwife, also observed that such a normal breech birth was ‘now hard to replicate within the UK’s National Health Service (NHS).’

In the OptiBreech Trial, we are trying to do just this: introduce a physiological breech birth approach into NHS practice settings, particularly obstetric units, and evaluate the outcomes. This has several potential advantages, including greater equity of access for more women, immediate access to the multi-disciplinary team (MDT) during birth, and shared learning throughout the MDT, with the potential to influence cultural changes.

But approaches to care (known as ‘complex interventions’ in the context of a trial) do not always work the same way in different settings. For example, physiological birth processes seem to work more efficiently the further one gets from an obstetric unit.7–10 Women who use NHS services have a much wider range of needs, complexities, birth philosophies and preparation levels than women who employ independent midwives. And greater involvement of the MDT means the physiological breech birth approach intersects with, and may conflict with, other cultural norms and practices. This may make it harder to implement some of its components, and potential conflucts may introduce additional risks.

Therefore, when testing a complex intervention in a trial, there is a need to clearly articulate each of the main components.11,12 This helps ensure those implementing the package of care know exactly what they are implementing. It also enables us to evaluate whether each aspect has been implemented as planned. We have observed that, although relatively simple itself, the concept of continuous cyclic pushing conflicts with current embedded cultural norms and assumptions about vaginal breech birth in many settings. An improvement in outcomes is likely to require a change in approach, but change can create uncomfortable feelings as teams deal with uncertainty in attempting a new approach.13,14 We hope to make the process of implementing continuous cyclic pushing, as a tool to support physiological breech birth, easier and safer by articulating the rationale and making visible some of the conflicting assumptions.

Description of the Technique

Continuous cyclic pushing: what it is and when it is used

Consistent with the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ guideline,21 we do not encourage active pushing until the breech is visible on the perineum, although we do not interfere with spontaneous maternal effort. This permits maximum recovery and fetal oxygenation between contractions. Continuous cyclic pushing begins when the birth attendant encourages the woman to push following the birth of the fetal pelvis. ‘Continuous’ refers to its use both during and between contractions until the birth is complete. ‘Cyclic’ refers to alternation between pushing effort and brief pauses for rest and breathing, resuming effort again when the woman is ready, regardless of whether a contraction is present. Following the birth of the pelvis, due to the high likelihood of cord compression, a significant pause between contractions is counter-productive for preserving fetal well-being.

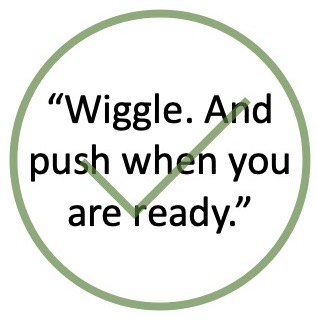

We are aiming to complete the birth within the intervals recommended in the Physiological Breech Birth Algorithm: within 7 minutes of rumping (+3 station), within 3 minutes of the birth of the umbilicus.3,15 Attendants support women through continuous cyclic pushing with language such as: “Well done. Now take a few deep breaths. Your baby is almost here. [brief pause for the deep breaths] And when you are ready, just collect your strength and push again.” In this way, it more closely resembles spontaneous pushing, in which women generally push three to five times per contraction, rather than directed pushing, in which women are instructed to take a deep breath at the beginning of the contraction and then hold it and bear down throughout the contraction.16

Once the fetal pelvis has passed completely through the perineum, there is often a short pause, much like there is with a head. The woman feels a release of pressure and sense of relief. She may stop pushing and take a few deep breaths, over a period of about 20 seconds. In an ideal physiological breech birth, the woman will have received no direction about pushing5 and will be completely tuned into her body, usually in a forward-leaning kneeling position. Following this natural pause, some women will continue to feel pressure and an urge to push, and they will simply collect their breath and do that when they are ready. If this doesn’t happen, the next contraction will occur within about a minute from the end of the previous contraction. Consistent with the available evidence,3,15 this process will be complete in an average (median) of about a minute and a half, and in most cases under three minutes, with no assistance required. The combination of maternal effort, movement and gravity is sufficient.

There are many examples of situations that deviate from the ‘ideal’ physiological breech birth described above. Being in tune with one’s body in labour and being supported to give birth without any directed pushing is very difficult to achieve in the hospital environment. It is routine practice in many hospitals to put women into lithotomy (supine, legs in stirrups) for a vaginal breech birth. Or she may have chosen an epidural, which will affect the Ferguson’s or fetal ejection reflex, even if it is a mobile epidural. Sometimes, there are concerns about the baby arising late in labour, such as the presence of late decelerations or a rising baseline on fetal heart auscultation, where one would not want the birth to take any longer than absolutely necessary. Intervals between contractions can also be longer than optimal, for example if the woman is exhausted in second stage or from the stress of undertaking an unplanned breech vaginal birth. Even well-meaning directions from the birth team can detract from the physiological birth process: “Now relax. Just breathe. And wait for the next contraction.” The woman’s attention is now focused on the attendant’s directions, away from the pressures and promptings of her own body, as she gains mastery over any spontaneous urge she may have, believing this is essential for her baby’s safety.

Many of us supporting physiological breech births within NHS settings have used continuous cyclic pushing in practice when we have observed the situation to be less than ideal for a completely physiological breech birth, for any of these reasons. And we have observed that, where there is no entrapment of arms or head, continuous cyclic pushing effects continuous progress. With the next episode of maternal effort, rotation begins and the legs are born, with the next effort the arms are born, etc. The head usually requires more than one episode of maternal effort, but with less time between. This similar to the ‘little pushes’ a midwife may coach a woman through as the head is being born in a cephalic birth, or the birth of the shoulders between contractions, guidance intended to optimise the perineal outcome. In either type of birth, when there is no entrapment, the process is not strenuous; it is simply effective. Furthermore, it is effective regardless of the woman’s birthing posture, but when upright, prompted maternal movement also assists descent and rotation, eg. ‘give it a wiggle’.

How does continuous cyclic pushing help us to identify complications early?

In contrast, strenuous effort and minimal or no progress is indicative of need for manual assistance. Consider the following scenario: the pelvis is born sacrum transverse as we would expect. Between contractions, the woman has no spontaneous urge to push. With the next contraction, a few centimetres of descent are observed, so that the baby’s knees are now born. No rotation has occurred. This repeats with the next contraction, two minutes later. With quite a bit of encouragement and effort during the contraction, the feet are finally born, about four minutes after the pelvis. The baby has still not rotated. The team await the next contraction, two minutes later. No descent occurs, and it is now very clear that the birth is complicated by a nuchal arm entrapment. Resolution of the entrapment is difficult because the baby has descended deeply into the pelvis with the arm extended, with less room and more resistance when rotational manoeuvres are attempted. The process takes three minutes. And then assistance is needed for the head. It is easy to see how the minutes add up, even when contractions continue to come regularly. And sometimes they do not.

Our observation is that, by encouraging continuous cyclic pushing, we can observe the signs of obstruction earlier, enabling us to intervene more quickly and effectively. In the above scenario, following the brief pause that occurs after the birth of the pelvis, if the woman does not resume movement and effort spontaneously within about 30 seconds, the attendant would gently encourage it (‘wiggle and push’). If pushing were strenuous and progress minimal, especially with no rotation, we would assume this was due to obstruction and deliver the fetal legs. We would again encourage the woman to collect her breath, and to ‘wiggle and push.’ If the next episode of strenuous effort did not result in the birth of the arms, we would assist this with rotational and other manoeuvres. And so on.

Potential conflicts with current practices

Applying cephalic birth ‘habits’ to breech births?

Each of us has seen in practice and in clinical reviews of adverse outcomes a tendency to instruct the woman to breathe and wait for the next contraction after delivery of the pelvis or arms. We consider that professionals may be doing what they would do in a cephalic birth. Following delivery of the head, there is (sometimes) a pause until the next contraction that delivers the body. During this time, reassurance is often given to the woman that she has done well and that with the next contraction she will have her baby.

A similar confusion may present itself when we observe ‘rumping’ to occur. Clinicians may think it normal to observe the presenting part for some time prior to the birth as this is what we may observe in a cephalic birth with no detriment to the fetus. But in a cephalic birth, only the head is in the pelvis. Due to the different mechanisms of a breech birth, once both buttocks remain on the perineum between contractions, the umbilicus is in the pelvis along with both the body and the legs. This increases the likelihood of cord occlusion and progressive acidosis if delay is not recognised and action taken. It is also very difficult to accurately assess the fetal heart rate with external monitoring when the pelvis and body are this deeply engaged.

Historical use of ‘wait for the next contraction’ as a breech-specific strategy

Very few trials have been done comparing different approaches to managing vaginal breech births. But in 1989, Arulkumaran et al published a trial in which they compared two techniques. In Group A (expediated breech delivery), “During one contraction and bearing down efforts, spontaneous expulsion of the buttocks were allowed up to the hip of the fetus so as not to deliver the umbilicus. Then the patient was requested to relax till the onset of the next contraction with the aim of delivering the whole fetus with the subsequent contraction.”17(p48) Group B was similar, but women were allowed to deliver the baby up to the shoulders, and a loop of cord was pulled down. The design of the trial was based on the assumption that fetal oxygenation is considered to be potentially impaired once the umbilicus is delivered, due to umbilical cord compression.18 Women gave birth in supine positions. The trial results were inconclusive. But ‘wait for the next contraction’ was part of a routinely interventive approach to managing a breech birth, contrasting with Evans’ repeated calls for “no directive pushing”5(p18) in physiological breech births.

Power from above is safer than pulling from below

The fundamental purpose of skill and technique with vaginal breech birth is to prevent progressive acidosis as much as possible, while avoiding the potential trauma of a quick or overly-manipulated delivery. To this end, the theme that power from above is safer than pulling from below repeats frequently in literature related to upright breech birth,19 the physiological breech birth approach,2 as well as many guidelines. The current Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) guideline on Management of Breech Presentation at Term explains, “Techniques to maximize power from above include effective maternal effort, hands and knees posture, the Bracht manoeuvre, and oxytocin augmentation.”20(p1201) Again, we need to consider the effects of context with regards to which sources of power from above we can effectively employ.

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists guideline does propose the use of the Bracht manoeuvre as an alternative,21 but this requires the woman to give birth on her back, which, when assisted by physiological breech birth-trained professionals, over three quarters of women do not do.22 To perform the manoeuvre, the attendant raises the legs and trunk of the baby over the mother’s pubic symphysis and abdomen, using an upwards movement without traction to achieve delivery of arms and fetal head. Of the Bracht manoeuvre, Professor Peter Dunn described, “[I]n this method, the obstetrician does little more than gravity would have achieved, had the woman been allowed to deliver in the natural upright position.”23(pF77) As UK midwives and obstetricians are not routinely trained in the safe use of the Bracht manoeuvre, we prefer to simply allow women to deliver in the upright position when they want to. And we supplement this with continuous cyclic pushing if appropriate.

In 2017, Louwen et al19 described 229 successful upright breech births in Frankfurt, where women gave birth in upright maternal birthing positions, usually hands and knees. The team provided a detailed description of their approach. To achieve power from above rather than below, they explained, “We rely on the mother’s contractions, but sometimes proceed to the use of oxytocin, and fundal pressure (the Kristeller manoeuvre)”19(psupp) (indications not given). While Louwen’s team’s work provides a precedent and example for upright breech hospital-based practice, this cannot directly translate to UK-based practice, in which the Kristeller manoeuvre is not routinely used, nor to the context of the OptiBreech Trial, in which most physiological breech births are led by midwives unless recourse to instrumental or surgical delivery is required. While the OptiBreech team members work closely with the MDT, oxytocin is not routinely prescribed for the purposes of increasing frequency and power of contractions around the time of birth. We cannot assume that without the total package of tools, or a replacement, we can achieve the same results.

Available evidence

Continuous cyclic pushing is a core skill taught in the Breech Birth Network’s Physiological Breech Birth training course. This is the only training programme focused on vaginal breech birth that has been evaluated including outcome data for actual breech births.22 Among 21 vaginal breech births attended by professionals who completed the training in 6 NHS hospitals, there were no severe adverse neonatal or maternal outcomes (using the composite definition used in the Term Breech Trial24), compared to a background rate of 7% among other breech births in the same hospitals, attended by professionals who did not complete the training. Additionally, among those 21 births, 11/21 (52%) of women had intact perinea.

We might compare this to available evidence concerning more invasive means of preventing delayed descent in a vaginal breech birth: oxytocin infusion and fundal pressure. Although both of these interventions are considered acceptable in different contexts,19,20 there is evidence that injudicious just could cause harm. Secondary analysis of the Term Breech Trial data indicated that the use of oxytocin augmentation increases risks in vaginal breech births.26 Concerns have also been raised about the risks associated with fundal pressure, especially when excessive force is used, including increased cervical and perineal tears, neonatal injuries and maternal dissatisfaction with care.27,28 While there may still be a place for the use of these interventions by experts, there is a need for high-quality evidence of their benefit before recommending them to the general population of practitioners in guidelines. When upskilling professionals who have had minimal exposure to and experience with vaginal breech birth, we prefer to start with less invasive interventions that are unlikely to cause harm and likely to be more acceptable to women who wish to have active births, in which they feel like a primary agent.

Discussion

As clinicians regularly attending vaginal breech births in NHS hospitals, we are satisfied that continuous cyclic pushing produces clear effects with none of the risks associated with preventable delay, if the next contraction is slow in arrival, or hands-on interventions applied before we have confirmed they are necessary.

In our approach, we rely heavily on maternal movement (enabled by upright postural positions), maternal effort, fetal effort (full body recoil flexion)2,3 and gravity to optimise the likelihood of an unassisted vaginal breech birth. Where the team considers it beneficial to minimise the time required for the baby to emerge, for any reason, the first intervention is always to encourage maternal movement and effort (‘wiggle and push’). This is recorded and evaluated as a fidelity measure in the OptiBreech Trial. With this approach, we recognise the locus of greatest efficacy lies within the mother-baby unit,2 and this is the first source of power we draw upon when a safe outcome appears to be at risk for any reason.

We therefore consider continuous cyclic pushing is an important tool for expediating the birth with minimal hands-on intervention, or for confirming in a timely manner that further intervention is required to achieve a safe outcome. We cannot yet make any claims that use of continuous cyclic pushing does or will increase the safety of vaginal breech births. But we hope by clearly described the practice itself, its rationale, and its relationship to alternative courses of action used in other settings, others may consider and evaluate its usefulness in their own practice.

References

1. Walker S, Scamell M, Parker P. Standards for maternity care professionals attending planned upright breech births: A Delphi study. Midwifery. 2016;34:7-14. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2016.01.007

2. Walker S, Scamell M, Parker P. Principles of physiological breech birth practice: A Delphi study. Midwifery. 2016;43(0):1-6. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2016.09.003

3. Reitter A, Halliday A, Walker S. Practical insight into upright breech birth from birth videos: A structured analysis. Birth. 2020;47(2):211-219. doi:10.1111/birt.12480

4. Walker SR, Parker PR, Scamell MR, Shawn Walker C, Nightingale F. Expertise in physiological breech birth: A mixed-methods study. Birth. Published online 2017:1-8. doi:10.1111/birt.12326

5. Evans J. Understanding physiological breech birth. Essentially MIDIRS. 2012;3(2):17-21.

6. Evans J. The final piece of the breech birth jigsaw? Essentially MIDIRS. 2012;3(3):46-49. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=jlh&AN=2011522453&site=ehost-live

7. Birthplace in England Collaborative Group. Perinatal and maternal outcomes by planned place of birth for healthy women with low risk pregnancies: the Birthplace in England national prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2011;343:d7400-d7400. doi:10.1136/bmj.d7400

8. Hastie C, Fahy KM. Optimising psychophysiology in third stage of labour: theory applied to practice. Women Birth. 2009;22(3):89-96. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2009.02.004

9. Buckley SJ. Hormonal Physiology of Childbearing: Evidence and Implications for Women, Babies, and Maternity Care. Published 2015. Accessed March 3, 2015. http://transform.childbirthconnection.org/reports/physiology/

10. Carpenter J, Burns E, Smith L. Factors Associated With Normal Physiologic Birth for Women Who Labor In Water: A Secondary Analysis of A Prospective Observational Study. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2022;00:1-8. doi:10.1111/JMWH.13315

11. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1687

12. O’Cathain A, Croot L, Duncan E, et al. Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e029954. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029954

13. Angus J, Hodnett E, O’Brien-Pallas L. Implementing evidence-based nursing practice: a tale of two intrapartum nursing units. Nurs Inq. 2003;10(4):218-228. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14622368

14. Leslie MS, Erickson-Owens D, Cseh M. The Evolution of Individual Maternity Care Providers to Delayed Cord Clamping: Is It the Evidence? Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health. 2015;60(5):561-569. doi:10.1111/jmwh.12333

15. Spillane E, Walker S, McCourt C. Optimal Time Intervals for Vaginal Breech Births: A Case-Control Study. Authorea Preprints. Published online September 24, 2021. doi:10.22541/AU.163251114.49455726/V1

16. Lemos A, Amorim MM, Dornelas de Andrade A, de Souza AI, Cabral Filho JE, Correia JB. Pushing/bearing down methods for the second stage of labour. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017;2017(3). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009124.PUB3

17. Arulkumaran S, Thavarasah AS, Ingemarsson I, Ratnam SS. An alternative approach to assisted vaginal breech delivery. Asia Oceania J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;15(1):47-51. Accessed February 2, 2018. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2735841

18. Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R. Expedited versus conservative approaches for vaginal delivery in breech presentation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;(6). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000082.pub2

19. Louwen F, Daviss B, Johnson KC, Reitter A. Does breech delivery in an upright position instead of on the back improve outcomes and avoid cesareans? International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2017;136(2):151-161. doi:10.1002/ijgo.12033

20. Kotaska A, Menticoglou S. No. 384-Management of Breech Presentation at Term. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 2019;41(8):1193-1205. doi:10.1016/j.jogc.2018.12.018

21. Impey L, Murphy D, Griffiths M, Penna L, on behalf of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Management of Breech Presentation. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2017;124(7):e151-e177. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14465

22. Mattiolo S, Spillane E, Walker S. Physiological breech birth training: An evaluation of clinical practice changes after a one‐day training program. Birth. 2021;48(4):558-565. doi:10.1111/birt.12562

23. Dunn PM. Erich Bracht (1882-1969) of Berlin and his “breech” manoeuvre. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88(1):F76-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12496236

24. Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, Hodnett ED, Saigal S, Willan AR. Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2000;356(9239):1375-1383. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02840-3

25. Battersby C, Michaelides S, Upton M, Rennie JM, Jaundice Working Group of the Atain (Avoiding Term Admissions Into Neonatal units) programme, led by the Patient Safety team in NHS Improvement. Term admissions to neonatal units in England: a role for transitional care? A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e016050. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016050

26. Su M, McLeod L, Ross S, et al. Factors associated with adverse perinatal outcome in the Term Breech Trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;189(3):740-745. doi:10.1067/S0002-9378(03)00822-6

27. Hofmeyr GJ, Vogel JP, Cuthbert A, Singata M. Fundal pressure during the second stage of labour. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017;2017(3). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006067.PUB3

28. Farrington E, Connolly M, Phung L, et al. The prevalence of uterine fundal pressure during the second stage of labour for women giving birth in health facilities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reproductive Health. 2021;18(1):1-17. doi:10.1186/S12978-021-01148-1/TABLES/6